Tommy Kendall: Higher Octane Learning

Words: Robby Pacicco / Photos: Stefano Facchin and FCA North America

When Roger Waters penned the lyrics to Pink Floyd’s classic rock anthem Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2), it was meant as a protest song towards the extremely strict regime found in boarding schools throughout the United Kingdom. Ironically, the double negative found within the opening verse “We don’t need no education” speaks for itself… education is needed. Yes, it’s become a staple within rock n’ roll being sung by children that have no idea who the Floyd are, to lifelong die-hard fans of the group. An incredible song from and incredible album, by an incredible band. The importance of education was not lost while growing up for the 2015 Motorsports Hall of Fame of America inductee, Tommy Kendall. The son of race car driver Charles Kendall, Tommy was born with the passion for competition in his DNA and the cliché need for speed. The racetrack beckoned him and wanted him as much as he wanted it. No stranger to a variety of race cars or race series, Kendall fit his tall frame into machines ranging from NASCAR Cup Series to the Bathurst 1000. He has even driven a rooster, seriously. You’ll be reminded to search for images online later on. His dominance of the SCCA Trans-Am Series during the 1990s had him claim four championships, including an impressive run in 1997 when he devoured 11 victories out of a potential 13. His talent doesn’t stop behind the wheel as he is also a very well-spoken and knowledgeable television personality. He has become a familiar voice for North American race fans as well as being “that guy” putting amazing cars through their paces then telling jealous drooling viewers all about it. With all his on track and on air success, he credits his pursuit of higher learning as his biggest motivator.

We’ll briefly interrupt this piece with a short interview with TK himself. Don’t worry, we didn’t forget about the rooster car.

DRM: Being the son of a racer yourself, racing is in your blood. When did you realize you wanted to make a career out of being a professional driver?

TK: I am going to date myself here, but if you think about what the world was like before the internet, kids’ worlds were limited by what they saw on the three TV channels and handful of magazines as well as things their friends and families were into. That is a long way of saying, I didn’t really know there was such a thing as being a race car driver until I was 12 or so. I knew I loved cars, motorbikes, go-karts, and going fast, but my world changed in 1980 when my dad bought a race car (Porsche 911 RSR) and we went to watch a friend, Pete Smith, race it at Sears Point. It was like my head exploded open and that was all I could think about from that point on. My dad saw this and told me it was not something you could make a career out of, but was fun and we could do some as long as I got good grades and went to college and did the same there. Needless to say, my focus on school improved at that point. Even though I was told it was impossible to make a living at it, it was almost all I thought about and started racing go-karts and then joined the Jim Russell Racing School series at Riverside Raceway. I did well there and began to focus on doing everything I could to be as successful as I could be at it. At this point, I could kind of see a way to make a career at it, but didn’t share that with my parents.

DRM: Many of us dream of being that “superstar” racer, and never really focus on a possible back up plan or alternate career. You raced and still remained focused on achieving your goal of securing a proper education at one of America’s best schools. How much pressure was that on you as a young man and how did you handle it?

TK: As I said earlier, my sponsorship so-to-speak, was totally tied to grades and then college. School was always relatively easy for me, but focus was a problem. Tying it to my racing was a masterstroke of genius by my parents and it came at just the right time in high school as I did well when I needed to and got into UCLA. While a sophomore at UCLA, I got a huge break to drive the factory-backed Malibu Grand Prix Mazda RX-7 that had won the previous two IMSA GTU titles. I made the most of it and won the championship and also the Firestone Firehawk championship in the same year (1986). I made some money and got signed as a paid pro the next year. My dad’s rules no longer applied, but it never occurred to me to stop school, and I stuck with it and eventually got my degree in 1991. I was always focused on the future so the pressure was mostly self-created and I always kind of thrived when things were hard. In retrospect, I kind of skipped adolescence, which isn’t totally healthy, but my desire to achieve was very strong. When I get asked by young kids today how to get started, I always encourage them to apply themselves, but not to be so focused on the future that they don’t realize how much fun the steps along the way are. It’s a tough balance, but I would have to say the pendulum of goal-setting and pressure on kids has really swung to the extreme and steals enjoyment from the things we initially loved. In almost all cases, I think it actually hinders performance because of the extreme fear of failure.

DRM: You’ve pretty much raced everything. Is there any particular car or cars that stood out to you?

TK: I have driven a pretty broad cross section of cars. They are all memorable for different reasons, but the ones that stand out are the Trans-Am cars for their near perfect blend of power, weight and aero. The 100-mile races were a perfect blend of intensity and rewarding the drivers and teams that could manage the tires best. From a pure thrill standpoint, I am so glad I got to drive in the heyday of GTP (Grand Touring Prototype). The cars were like fighter jets on the ground. A 44 second lap around Lime Rock is something I will never forget! The Bathurst 1000 also stands out as perhaps the most memorable single event. The V8 Supercars are similar to Trans-Am cars in their blend of power and grip, but to take on a track like Mt. Panorama never having seen it, in a right-hand-drive, left-hand-shift car against that level of competition was as big a challenge as I have ever had. 7th place didn’t seem great at the time, but Rookie of the Year and highest finish even to this day for an American became a career highlight.

DRM: Now, as a broadcaster and known TV personality, you get to enjoy the automotive and motorsport scene without the crash helmet. How was the transition for you?

TK: My transition to the TV booth was the opposite of my racing career, where I left nothing to chance and maxed out every lead. I literally fell into it when a guy I knew, Steve Beim, got a chance to fill in as the producer (he was already the director) for a CART race in 1997. It was towards the end of my big win streak and I was getting a lot of attention. He thought I’d be good in the booth and sold his bosses. I just kind of let it rip, because I didn’t really care and I sensed people were ready for a little more authentic delivery. I did a handful of races the next year and that really got me started. The transition was pretty easy as I was talking about something I knew so well, but the challenge was to maintain the loose, carefree approach even when I did start to enjoy and care about it. I have always had a little mantra before going on the air to remind me to let it rip. I tell myself, “Try a little bit to get fired today.” I have succeeded on occasion, but the fans appreciate it and ultimately I work for them.

DRM: You’ve been there, you know how it is on the track. Do you find your time as a racer allowed you to be more subjective as a broadcaster?

TK: There is no question that my total obsession with all aspects of the sport prepared me really well for broadcasting. Like anyone who obsesses over something, you pick up a lot that is not obvious to others. My approach was different compared to a lot of drivers, but it gave me a deep understanding of how everything worked, and I was totally conscious of the various drivers of performance too. That allowed me to explain things in layperson terms and also see things unfold more clearly. That said, I also like to have fun at the appropriate times and striking the right balance between information and entertainment is a tricky one. It is easy to overshoot one way or the other and also to forget how serious this business can be, when fun is the furthest from people’s minds.

DRM: It must have been a special feeling teaming up with Viper for 2013, getting back in a race car?

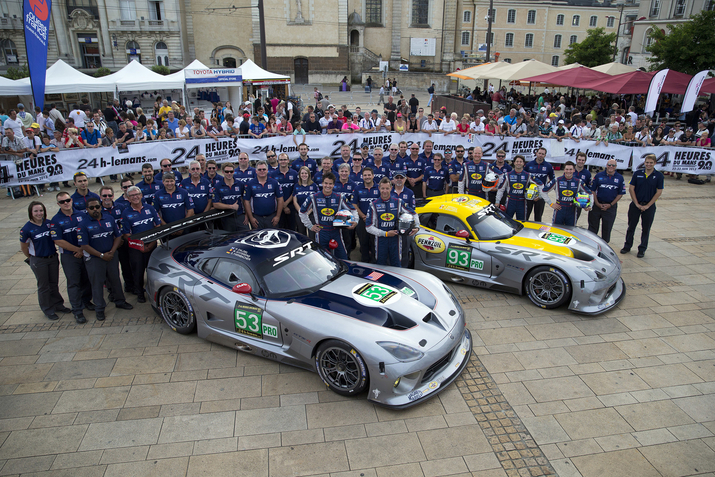

TK: The Viper deal was a most pleasant surprise and an amazing experience. I was actually trying to get Brian Vickers into the car as he was left ride-less when Red Bull pulled out of NASCAR, and I urged him to pursue all the racing he never had time for. Le Mans was on that list. I took him to the NY Auto Show and introduced him to all the SRT executives at the reveal. A couple weeks later, Bill Riley called me and said, “What about you?” I said, “Me? I am out of shape and haven’t driven in years.” I had always told people I was open to driving again, but only in a top team with proper backing. Those things don’t tend to find you if you aren’t beating the bushes though, so I assumed I never would. Needless to say, all my conditions were satisfied in the Viper program, so I agreed to test for the seat. I wish I had a year to prepare as it takes a while to get fit and get fully sharp again, but I don’t regret doing it as Le Mans was amazing and so was being part of a special car’s history with a special group of people. It was kind of nice farewell tour of sorts, which I didn’t get with my stopping so abruptly in 1997.

DRM: Do Rev Mi is about cars, music and motorsports. Do you have any musical talents? Or did you ever dream of being on stage instead of on a starting grid?

TK: Everyone dreams about being a rock star at one point once you see how much girls like rock stars. But I quickly discovered that my main musical talent was in understanding that I had no musical talent! Having no talent isn’t a crime, but thinking you do can be painful for others. I had to take piano lessons for several years and about all that remains from that is a couple verses of “We Three Kings.” Thankfully, the machines I drove made some beautiful sounds so I get credited with creating some memorable music anyways.

DRM: Racing is all about timing, like music. RPM can refer to an engine or a record player. Was there any specific type of music you’d listen to when training or preparing for the races?

TK: I enjoy all types of music, and growing up in LA around some people in the industry, I have gotten to see a number of bands live early in their careers. Oingo Boingo opening for the Police, Violent Femmes when they first hit the scene, English Beat played at our high school, and The Clash performed in a small theater my dad owned in San Diego. Our family road trips to Havasu featured a fair bit of country and singer songwriter types. 8-track tapes were limited, but I remember Jim Croce, Willie Nelson, David Allen Coe, and Dr. Hook playing over and over across the desert. When I raced, my problem was never getting fired up, it was usually trying to not get too amped up and manage the stress and pressure. I was usually trying to relax to prepare so I defaulted to that type of music, almost like the musical version of comfort food. Jimmy Buffet was a mainstay for me during my racing career for the same reason and I saw him in concert all over the country.

DRM: With all your knowledge and experience on and off the track, what advice would you give to someone willing to put in the time and effort to become a professional racer?

TK: When asked for advice on making racing a career, I always start with, “Don’t!” I say that because it is so hard and full of disappointment. It is literally the only thing I can think of where talent guarantees you nothing. Having said that, I then say, “If it is all you can think about, you owe it to yourself to give yourself the best chance you can and that means learn absolutely everything you can. This doesn’t just mean developing your driving skills, it also means understanding the car and its dynamics as well as you can, and today, learning how to find money is perhaps as important as all of that. I used to think about how good my car would look in a certain sponsor’s colors. That’s great, but figuring out how to solve the problems that the executives at that company lose sleep over is where the real magic lies. Everyone talks about exposure and business-to-business, which matter, but everyone does that. If you think about how to solve their big problems, you will have plenty of sponsors. Finally, I touched on it earlier, all that focus on preparation and performance can make you lose sight of why you got into it in the first place, because you love it. If you don’t actively try to enjoy the process of climbing the ladder, you will miss it and with no guarantees there will be a next step, so try to relish each step.

DRM: Lastly, is there any particular driver you competed against or have watched compete that you especially admired?

TK: I could go on and on here. From Dennis Aase to John Paul Jr. to Klaus Ludwig to Rick Mears, Keke Rosberg, Roberto Guerrero, Al Unser Jr., the list is long of early heroes. Like most, I idolized Ayrton Senna and had the pleasure of seeing him race in his home grand prix in 1988, which was like a religious experience for a racer. I spent a lot of time with Dale Earnhardt Sr. when I was doing some of my early NASCAR races and struck up a unique and special friendship. Like everyone, I looked up to him big time, but it was strangely mutual because of my degree at UCLA and the fact that his dropping out of school in 9th grade caused a rift that never healed with his dad. I used to tell him, he was smarter than people I knew with 3 degrees, but I know it always bugged him. As for contemporaries, I was fortunate to race against such a great group of drivers in that era of Trans-Am and IMSA. O’ Connell, Ribbs, Pruett, Brassfield, Sharp, Schroeder, Baldwin, Said and many I left out were all stars and any could win on any given day, but the most complete driver I raced against was Ron Fellows. He literally never stopped improving his whole career and was fast on all types of tracks, in all types of conditions, & didn’t seem to have off days. My battles with him stand out as my most memorable and wins against him the most satisfying.

His poetic approach to education allowed him to develop into the person he wished to be and worked so hard to become. Easily, TK could have turned Alice Cooper’s School’s Out into his own personal theme song when he started winning, but the smart man proved wise not to. He finished what he started. His teaching words of advice and sharing of knowledge to the bright eyed up and comers and sadly may-never-be-ers is a true indication that the student has become the master. It’s safe to say, TK has eaten his meat and deserves his pudding. Pink Floyd would agree, whoever he is.

Alright, now you can all go ahead and search online for Tommy Kendall’s El Gallo Grande. You’re Welcome.